With thanks to all the artists, labels, and promoters who sent their projects to me this month, I’ve compiled a list of some of my favorites. There were even more releases than the 50 or so I listened to this month. I’ll be writing separate pieces on the October releases by Elsa Nilsson and Aruán Ortiz; and Ron Blake, Antoine Drye, Chien Chien Lu, and Simon Moullier. (Those will get posted soon; I’m a bit behind because I’m premiering three new research presentations during this Fall conference season and conducting lots of interviews for my book project.) Also check out the new work of Billy Mohler, Quinsin Nachoff, and Kevin Sun. And, however you’re able to, lend these musicians your support not just with streaming their music, but buying it…and tickets to their shows, and their merch.

Feel free to share your favorites from this month in the comments below and if there’s an upcoming release that you’d like me to feature, you can reach out here.

Thanks for reading!

The Month in Review – October 2023

JD Allen, This (Savant), released October 20th.

There’s a lot of conversation around THIS as a “departure” for saxophonist JD Allen. I don’t quite hear it that way. Maybe it’s a departure in that Allen hasn’t recorded with an electronics artist before, but that’s about it. Allen’s music has always been about dialogue, and even with the most “traditional” projects, there’s always been an Afrofuturist element to his work: a deeply rooted and expansive critical take on pushing things forward. Maybe it’s because of Alex Bonney’s electronics that this aspect of Allen’s music is more audible here. THIS is insistent music, starting with a call to gather. The trio (Allen, Bonney, and drummer Gwilym Jones) play with processing and distance, fading in and out on waves of sound. At times Allen grabs hold of the music and listeners with his torrential, blues-based bebop lines. It’s in these moments when Bonney’s presence can be most surprising. Those familiar with Allen’s music will recognize his extended improvised duets with drummers, but Bonney adds layers and layers of sonic intrigue: some times in stark contrast, at other times with a surprising contextual turn or a lingering remnant that extends the phrase. At all times, though, Bonney is integral to the trio and the album’s success.

THIS is also highly melodic music. The trio is constantly at-work manipulating and developing sound ideas through polyphonic (and interactive) layering. Timbrally Bonney’s presence may be a departure for Allen but there’s a long history of jazz (and/or Black American music) and electronics. And even longer traditions of improvised music attuned to “atmospheric” or “environmental” sounds. Though we may hear Bonney’s contributions as otherworldly, they are very much rooted in Earthly technologies. And Allen doesn’t hesitate for a moment in this sonic sphere. If you only listen to one track, go to “Mx. Fairweather,” a study in contrasts with Allen’s bebopping phrases bouncing along unfazed and unfettered by electronics that surge, growl, and belch, spanning from the under/worldly to the celestial, from earthy acoustics to the unimaginably synthetic — held together by Jones’s steady New Orleans street beat. THIS is a masterful album.

Caroline Davis, Alula: Captivity (Ropeadope), released October 13th.

Like Allen’s record Alula: Captivity foregrounds technological timbres and environmental soundscapes folded into the mix. Those elements — crafted by Val Jeanty — are essential to the power of saxophonist Caroline Davis’s latest record. (I just interviewed pianist Sumi Tonooka for my book; she has a new project with Jen Shyu and Jeanty, so I really enjoyed spending more time with Jeanty’s work this month.) This is music with a message, an expression of Davis’s historically informed study of and activism related to carceral states. This album is heavy music that confronts, cajoles, and conjures worlds of historical epochs, our multiple presents, and future imaginaries for a New Way of Life. It’s the business of Afrofuturists, activists, and artists alike.

There are many (many!) moments of compositional, improvisational, and ensemble magic on this album: on “and it yet it moves,” a composition that ruminates on Galileo’s fate, Davis executes elliptical orbits around the band, altering a melodic cyclic ever so slightly in each iteration; on “synchronize my body where my mind has always been” Davis manifests collectivity amid complicated and complex bodies/beings through a series of amazing duets with her bandmates; the joy of “the promise i made,” fueled by Jeanty; and the moving hymn, compelling artistry, clarity of vision, and sheer impact of “put it on a poster,” Davis’s tribute to Sandra Bland. One constant — an accumulation of similar, surprising moments throughout the album — was Davis’s work as an accompanist, a role usually not relegated (let alone adopted!) by a saxophonist. In stunning moments of emergent sonic synchrony that demonstrate not just superior musicianship but also the power of music to enact equitable social relationships, Davis highlights the artistry of her ensemble’s comping around her through her own playing.

There are messages that accompany this music, too: some are apparent from samples and the music’s insistent qualities, but listeners should seek this work out. Davis’s study pays off in superb artistry but the message — and the call to carry to the message — warrant more attention and action. The power of music to affect social change will never be realized unless listeners are moved to act.

Flying Pooka, The Ecstasy of Becoming (Alma), released October 6th.

The Ecstasy of Becoming is joyous and tricky. The musicians — pianist Florian Hoefner and saxophonist Dani Oore — were new to me. The album is comprised entirely of improvisation — no set melodies, no through-composed passages, no premeditated arrangements. This practice isn’t especially remarkable but the results on Ecstasy are stunningly lyrical and dynamic. A third sonic element — Oore’s raw, whimsical singing — adds a timbre and approach that are neither imitative nor derivative. Oore highlights the human voice as another instrument in the ensemble rather than suggesting any semblance of a “traditional” jazz vocal performance practice. In fact, the listener can hear the work that Oore has done to meld the timbres of his voice and saxophone together, producing magical moments when you’re left wondering where one ends and the other begins. The Ecstasy of Becoming is full of highly inventive and engaging music. At times wondrously improvised, the development, organization, precision and clarity of ideas, and arcs of the music betray a deep connection between the musicians. Hoefner and Oore cover a wide range of sounds and genres, with imagination, intriguing and responsive dialogue, and expert musicality as the unifying factors. At times calming and lushly melodic, at others playful and noisy, as Flying Pooka the duo plays fugues, jams, grooves and vamps; ballads that bounce and others that caress; dances that haunt, lurk, and seep; and others that flutter and float. Be sure to add the album’s penultimate track, “Death Dances,” to your All Hallow’s Eve/día de los muertos soundtrack.

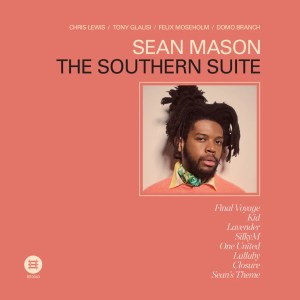

Sean Mason, The Southern Suite (Blue Engine), released October 27th.

In The Southern Suite Sean Mason conjures an entire history of gospel and blues-heavy romps — recalling some of the Cyrus Chestnut and Christian McBride albums from the late 1990s and early 2000s, and earlier heydays of 1930s Kansas City, and 1950s hard bop, and 1960s soul jazz. The Charlotte-born, self-taught pianist applies his studies to an album that offers an updated take on a long history traced back to Earl Hines, Jelly Roll Morton, and Scott Joplin. There are allusions to Ellington and Horace Silver in his playing, too. For all the time-traveling and historically accurate citations, though, this record is just plain fun — full of joy, backbeat, and bouncing horn lines — spanning the whole gamut from laid back Basie cool to Mingus’s polyphonic church hollers. It’s a credit to Mason as a writer, pianist, and bandleader that he navigates this history so deftly while weaving together a wholly personal vision for his debut record via all original compositions — carefully tending to the traditions while cultivating his own artistic voice. I’m really looking forward to what’s to come.

Allison Miller, Rivers in Our Veins (Royal Potato), released October 6th.

I love everything about this record. It’s wide-ranging with thoughtful compositions that show off the musicality of all the ensemble members. It carries with it timely and essential messages related to water rights and ecological awareness. And there are tap dancers. Listening to Allison Miller’s Rivers in Our Veins feels like an infusion of energy that will get you up and dancing, and at times will sweep you along in its currents. Clarinetist Ben Goldberg shows up on two records this month for his contra-alto clarinet playing. (Prepping the review I’d continuously start listening again in the middle of the album — with “Fierce,” a track that features Goldberg — just to spend more time with his stunning solo work.) “Blue Wild Indigo” features a remarkable solo by Miller after yet another vamp section (a compositional device that Miller uses so effectively throughout the album as accompaniment for various soloists, including tap dancers). Goldberg’s playing at the beginning of “Shipyards” is tremendous, a masterclass in extended techniques. The interplay with tap dancers on the same track — within a pointillistic and polyrhythmic vamp structure — highlights Miller’s thoughtful integration of dancers into the ensemble. The following track, the lovely “Riparian Love,” offers a stark contrast: the range Miller shows as composer and the honesty of all the emotions her music evokes are mesmerizing. If you give in to it, this record will pull you in again and again. (For more on the album, check out this recent Across the Margin podcast episode with Miller.)

Ethan Philion, Gnosis (Sunnyside), released October 6th.

In Gnosis bassist Ethan Philion meditates on group improvisation as a form of transcendent knowledge. After his debut album devoted to Mingus, Philion and his ensemble mainly work through the leader’s original compositions. The one cover is a Mingus tune — “What Love” — and Mingus’s legacy and influence (as composer, bandleader, and bassist) are clearly audible throughout; however Philion has most assuredly moved into his own in all those regards. From a purely auditory perspective, Gnosis is one of the records I most enjoyed listening to this month. The group’s rapport is evidently strong with plenty of examples of deep listening and responsiveness (see “Sheep Shank”). The contrast between “Nostalgia,” the comforting ballad, and “Comment Section,” the noisy and disjointed free piece is brilliant; and yet both pieces are similarly remarkable in how the ensemble’s playing so convincingly evokes the moods and emotions associated with each of those titles. The album’s closing track — the title track — builds up to a climactic ending. Gnosis is a solid offering that very likely is going to end up in my permanent rotation.

Angelica Sanchez Nonet. Nighttime Creatures (Pyroclastic), released October 26th.

This record might be the perfect soundtrack for All Hallow’s Eve/día de los muertos but, in truth, any day is a great day to listen to Nighttime Creatures. Angelica Sanchez’s imaginings of the nightworld after our sight fails us is a triumph in every sense. I am transfixed by this record, in part because of how Sanchez’s composed passages flow so seamlessly into the ensemble’s improvisations. It’s a great credit to both her as a bandleader/composer and to the other musicians for how completely they integrated their individual offerings into her artistic vision. Sanchez captures so many nighttime moments — the melancholy, the frenzy, the calm, the contemplative, the hushed, and the cacophonous — with an expert cast of musicians (including Ben Goldberg). In the album’s press materials, the composer invokes Ellington as an influence which comes through so clearly in how masterfully Sanchez manipulates timbres and arranges the polyphonic interplay of her nine-piece ensemble, while also writing passages that highlight the unique approaches of each musician.

The magic of this record lingered with me all month. I took the opportunity to call Sanchez and talk to her about some aspects of it, and I’m so glad I did. We had a lovely conversation about teaching, listening, mentorship, and her compositional process. When I asked about blurring the lines between improv and through-composed passages, she responded that she’s been working on just that for 30 years. How fortunate we are to hear the fruits of that concentrated labor on this album. In addition to talking about Ellington — and the importance of writing “for people, not instruments” — Sanchez mentioned Mary Lou Williams and in particular her indebtedness to the recently departed Carla Bley who was a close friend, model teacher, and caring mentor to Sanchez. (“CB Time Traveler” is dedicated to Bley.) Nighttime Creatures takes its inspiration from the after-dark world around Bard College, where Sanchez now continues the lineages of Williams and Bley working with and inspiring the next generation of students.