[Editor’s note: I’m grateful to my friend and colleague Ben Barson — saxophonist, jazz studies scholar, and author of the new book, Brassroots Democracy: Maroon Ecologies and the Jazz Commons — for contributing this review of Obed Calvaire’s recent release. As the U.S. grapples with yet another wave of anti-immigrant and anti-Haitian rhetoric and violence, listening attentively and with care to this album’s messages and the musicians who carry them is essential for moving forward with more tolerance. Thanks also to Obed Calvaire for dialoging with Ben, and to Lydia Liebman who introduced me to the album and facilitated the conversation with Obed. – MJL]

…! …! …!

Obed Calvaire’s 150 Million Gold Francs (ropeadope) is a masterful blend of Haitian music and contemporary jazz, offering a profound sonic exploration of Haiti’s cultural and historical legacy. The album seamlessly integrates traditional rhythms like compa, catá, and yanvalou with swing, synthesizer-heavy fusion, and contemporary production techniques.1 Calvaire’s unique compositional concept creates a soundscape that honors Haiti’s world-historic revolution, laments its current crisis, and looks toward the horizons of an emancipated future.

for a link to purchase.

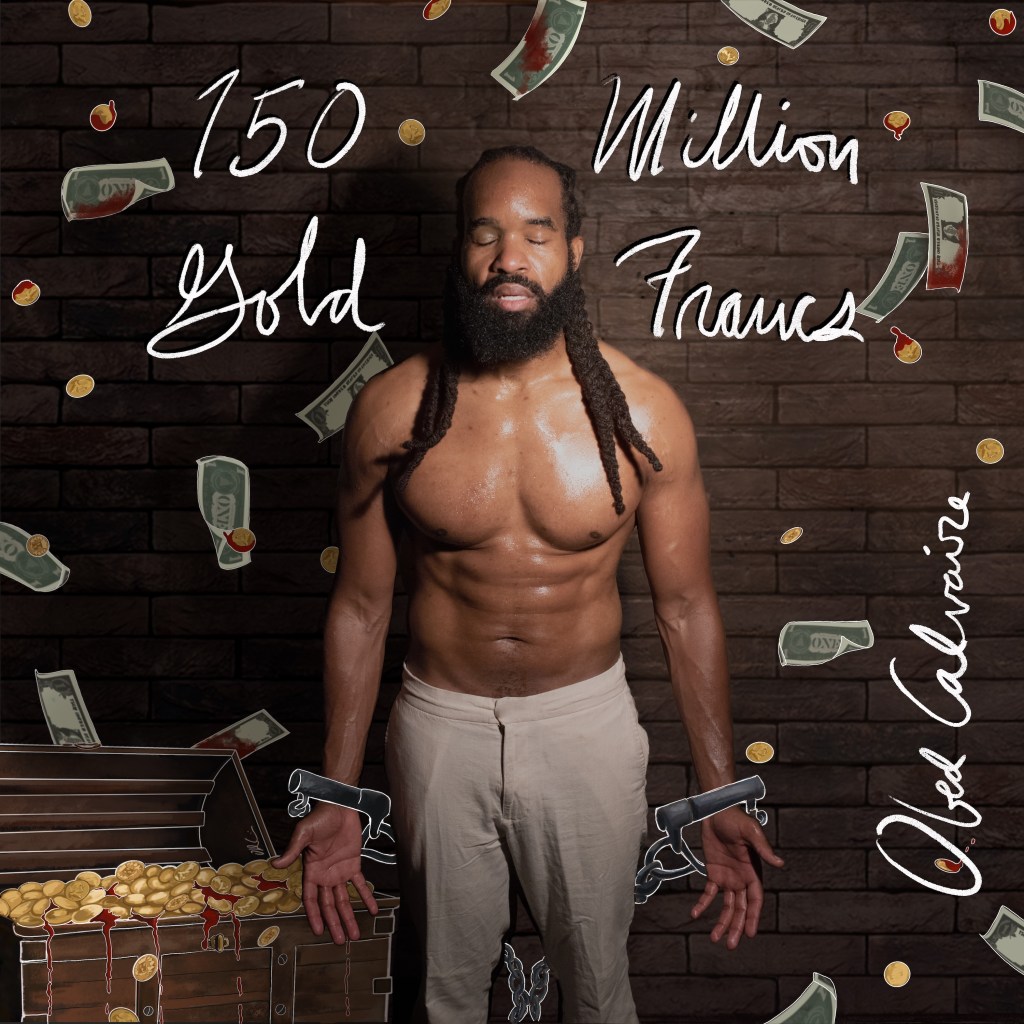

(Cover Photo and artwork by Jasmin Ortiz Gonzalez. Photo by Lawrence Sumulong)

150 Million Gold Francs, Ropeadope, 2024. Personnel: Obed Calvaire, drums; Godwin Louis, alto sax; Harold St. Louis, keyboards; Dener Ceide, guitar; Sullivan Fortner, piano and organ; Addi Lafosse, electric bass; Jonathan Michel, bass (tracks 1 & 4). Tracks: Sa Pa Fem Anyen; Just Friends; Haiti’s Journey; Sa Nou Fe Nap Peye; 150 Million Gold Francs; Gaya Ko W; Na Pwen Miray Lamou Pap Kraze. Recorded in New York, NY, at Seer Sound. obedcalvaire.com/.

Born of Haitian parentage in Miami, Calvaire, who does not overdub or have a hand percussionist playing on the album, demonstrates his drumming prowess and shines as both a composer and performer throughout 150 Million Gold Francs. His use of a yanvalou pattern on the cowbell (which bears a semblance to a cinquillo pattern) in the beginning of “Haiti’s Journey,” while the bass drum and snare are active, is one example of this. Over this polyrhythmic groove, saxophonist Godwin Louis plays a bright, lyrical saxophone-motif that soars over the groove. Suddenly, an EQ filter envelops the band, futuristic synths creep in at the extremes of the audio spectrum, and Louis begins playing double-time phrases evocative of Dolphy or Coltrane through a distortion and wah pedal that evokes an uncanny sense of doom. Then the effect fades, and Dener Ceide’s arpeggiated guitar line plays over what Obed calls a “6/8 African section,” setting the tone for an energetic and even utopic resolution. As Calvaire explained in his reasoning behind the song—to evoke the long passage of Haitian history:

“The beginning is very, very melodic. Just picture a woman with her flowery dress, with a basket of fruit on her head, walking to the market, the farmer’s market, where one can buy all types of whatever goodies and vegetables. Kids are going to school the next day with ties, right uniform press, all the creases are nice and crisp. That’s when you hear the distortion sounds, that’s when a lot of the murders, murders committed by Papa Doc, attempting to commit genocide against mulattos….that was the beginning of the end.”

In other songs, not only polyrhythm but overlapping time-signatures are implied and referenced. This is the case in the album’s opening track, “Sa Pa Fen Anyen,” which begins with a recorded sample of his mother’s voice from a revival prayer, and under which enters Calvaire’s catá-based groove while bassist Addi Lafosse plays a bold tritone-based bass line. While played in 4, Calvaire explains that “In ceremonies, the catá extends in 5. Groupings of 4 that can be elastic in 5.” This elasticity is captured in this song, as a 5-beat grouping underlays the 4/4 time signature in multiple voices, until pianist Sullivan Fortner surprisingly breaks with the form and begins playing whole-tone clusters. This ending was entirely improvised, allowing Calvaire to conclude the song with one of his best drum solos on the album: “It was a blessing in disguise,” he explains to me.

Because these transitions are often cued by the dramatic, yet nuanced and seamless, changes in rhythmic feel and arrangement texture, Calvaire’s rhythmic interplay reflects not only technical mastery but his narrative framing of Haitian history. His compositions point to different historical periods and emotional states. In the album’s title track, “150 Million Gold Francs”, Harold St. Louis’s dark and brooding keyboard solo unfolds over modal-based minor progression, finally giving way to what sounds and feels like rara-procession. (Rara is a processional form developed in rural Haiti, where theatrical-musical mobilizations travel through distant villages and urban centers alike.) Here saxophonist Godwin Louis, by manipulating his embouchure and through the clever use of multiphonics, transforms his instrument into what sounds like a Vaskin, a bamboo trumpet used in rara ceremonies. A large vocal ensemble that enters soon after, and which leads a call-and-response section, further echoes the communal spirit of Haitian rara. Louis masterfully blends his tone into the vocal chorus on his horn, creating a true sense of dialogue and a merging of worlds. All of this generates an affect that rara parades can uniquely create—of which Haitian American novelist Danticat once explained: “At last, my body is a tiny fragment of a much larger being.”2

Poignant lyricism, emotion, and energy on the part of the soloists only augment this sensation, all within a song whose very title—“150 Million Gold Francs”—is a testament to the historic robbery of Haiti as it was forced to pay France for the “crime” of casting off the shackles of slavery on the eve of independence. (The New York Times reports today that this amount today would be valued at close to 115 billion dollars.) The album’s very cover makes this connection explicit: its striking cover art, designed by Jasmin Ortiz Gonzalez, portrays Calvaire bare-chested with his eyes closed, his hands bound in front of an illustration of the stolen bounty. “It symbolizes how we have nothing else to take,” Calvaire says, “how we are still locked into this slave mentality.” Calvaire hopes his music can break that bondage. “I’m not trying to force anyone who’s on a particular side. I want to focus on how we can be better human beings.”

Not every song on the album is intended to carry such weight. While every song takes listeners on a listening journey through Haiti’s resilience, some celebrate the joys of community and friendship. On his arrangement of “Just Friends,” which begins with a ballad opening between Louis and Fortner, emerges as a buoyant medium-tempo interpretation, full of unconventional voicings and a uniquely patterned swing. The heavily chorus-effected guitar of Dener Ceide joins the ensemble as Louis performs a brilliant and tasteful solo, and a quasi-montuno piano accompaniment becomes prevalent. After his third chorus, a complex modulating melodic line is played in unison by each musician, and this gives way to an exciting compa breakdown. Here, a heavily effected synthesizer solos over a complex interaction that Calvaire orchestrates, as he plays three different rhythmic patterns on four different drums: compa on a stack cymbal, a conga rhythm on the snare, and a “gong” rhythm on the cowbell and floor tom. This song, according to Calvaire, is a way to acknowledge “the friends I grew up with,” who, with the exception of Fortner, are all of Haitian descent. “On this album, we are coming together as a community.” This long history of playing together in a variety of contexts—church, jazz, and popular Haitian music—explains the band’s ability to change feels on a dime. The creative and limber tightness of these musicians is electrifying, and creates just that feeling of community that Calvaire hoped to summon.

150 Million Gold Francs is a significant cultural statement—a call to embrace both heritage and innovation, while not flinching as we bear witness to a historic crisis in our midst of immense suffering with imperial overtones. True to the spirit of the work, the album cannot be streamed in full on Spotify in protest of the streamer’s business model and its CEO’s recent comments. Instead, you can listen to and purchase the album on bandcamp. Calvaire’s work is a testament to the power of music to educate, inspire, and bring communities together in service of a more human future, even and especially when political solutions feel exhausted.

…! …! …!